Abstract

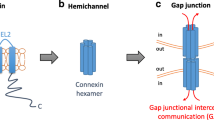

Gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) is a form of cell–cell communication mediating the exchange of small molecules between neighboring cells. Gap junctions (GJs) are formed by connexins (Cxs), and are subject to tight and dynamic regulation. They are involved in the cell cycle, differentiation, and cell signaling. The loss of Cxs and GJs is a hallmark of carcinogenesis, while their induction in cancer cells leads to a reversal of the cancer phenotype, induction of differentiation, and regulation of cell growth. On the basis of the observations about Cx loss in breast cancer, this review examines Cxs' involvement in breast cancer metastasis. Previous work indicates that Cx expression is inversely correlated to metastatic potential. This is probably because of the loss of cooperation between neighboring cells, leading to cell heterogeneity and cell dissociation in the tumor. The possible involvement of Cx activity during metastasis will be discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

J.W. Holder, E. Elmore, and J. C. Barrett (1993). Gap junction function and cancer. Cancer Res. 53:3475-3485.

J. E. Trosko and R. J. Ruch (1998). Cell-cell communication in carcinogenesis. Front Biosci. 3:D208-D236. (Process Citation)

D. A. Goodenough, J. A. Goliger, and D. L. Paul (1996). Connexins, connexons, and intercellular communication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:475-502.

M. Zhang and S. S. Thorgeirsson (1994). Modulation of connexins during differentiation of oval cells into hepatocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 213:37-42.

P. Monaghan and D. Moss (1996). Connexin expression and gap junctions in the mammary gland. Cell Biol. Int. 20:121-125.

A. Pozzi, B. Risek, D. T. Kiang, N. B. Gilula, and N. M. Kumar (1995). Analysis of multiple gap junction gene products in the rodent and human mammary gland. Exp. Cell Res. 220:212-219.

S. Jamieson, J. J. Going, R. D'Arcy, and W. D. George (1998). Expression of gap junction proteins connexin 26 and connexin 43 in normal human breast and in breast tumours. J. Pathol. 184:37-43.

D. Locke (1998). Gap junctions in normal and neoplastic mammary gland. J. Pathol. 186:343-349.

P. Monaghan, C. Clarke, N. P. Perusinghe, D. W. Moss, X. Y. Chen, and W. H. Evans (1996). Gap junction distribution and connexin expression in human breast. Exp. Cell Res. 223:29-38.

E. C. Beyer, D. L. Paul, and D. A. Goodenough (1987). Connexin43: Aprotein from rat heart homologous to a gap junction protein from liver. J. Cell Biol. 105:2621-2629.

A. G. Reaume, P. A. de Sousa, S. Kulkarni, B. L. Langille, D. Zhu, T. C. Davies, S. C. Juneja, G. M. Kidder, and J. Rossant (1995). Cardiac malformation in neonatal mice lacking connexin43. Science 267:1831-1834. (comments)

G. I. Fishman, R. L. Eddy, T. B. Shows, L. Rosenthal, and L. A. Leinwand (1991). The human connexin gene family of gap junction proteins: Distinct chromosomal locations but similar structures. Genomics 10:250-256.

T. Toyofuku, M. Yabuki, K. Otsu, T. Kuzuya, M. Hori, and M. Tada (1998). Direct association of the gap junction protein connexin-43 with ZO-1 in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12725-12731.

H. Yamasaki, M. Mesnil, Y. Omori, N. Mironov, and V. Krutovskikh (1995). Intercellular communication and carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 333:181-188.

M. M. Atkinson, P. D. Lampe, H. H. Lin, R. Kollander, X. R. Li, and D.T. Kiang (1995). CyclicAMPmodifies the cellular distribution of connexin43 and induces a persistent increase in the junctional permeability of mouse mammary tumor cells. J. Cell Sci. 108:3079-3090.

H. Guo, P. Acevedo, F.D. Parsa, and J. S. Bertram (1992). Gapjunctional protein connexin 43 is expressed in dermis and epidermis of human skin: Differential modulation by retinoids. J. Invest. Dermatol. 99:460-467.

J. S. Bertram (1999). Carotenoids and gene regulation. Nutr. Rev. 57:182-191.

Y. S. Jou, B. Layhe, D. F. Matesic, C. C. Chang, A. W. de Feijter, L. Lockwood, C. W. Welsch, J. E. Klaunig, and J. E. Trosko (1995). Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication and malignant transformation of rat liver epithelial cells by neu oncogene. Carcinogenesis 16:311-317.

A. Hofer, J. C. Saez, C. C. Chang, J. E. Trosko, D. C. Spray, and R. Dermietzel (1996). C-erbB2/neu transfection induces gap junctional communication incompetence in glial cells. J. Neurosci. 16:4311-4321.

M.Y. Kanemitsu, L.W. Loo, S. Simon, A.F. Lau, and W. Eckhart (1997). Tyrosine phosphorylation of connexin 43 by v-Src is mediated by SH2 and SH3 domain interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22824-22831.

L. W. Loo, J. M. Berestecky, M. Y. Kanemitsu, and A. F. Lau (1995). pp60src-mediated phosphorylation of connexin 43, a gap junction protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12751-12761.

A.W. de Feijter, D. F. Matesic, R. J. Ruch, X. Guan, C.C. Chang, and J. E. Trosko (1996). Localization and function of the connexin 43 gap-junction protein in normal and various oncogeneexpressing rat liver epithelial cells. Mol. Carcin. 16:203-212.

D. W. Laird, P. Fistouris, G. Batist, L. Alpert, H. T. Huynh, G. D. Carystinos, and M.A. Alaoui-Jamali (1999). Deficiency of connexin43 gap junctions is an independent marker for breast tumors. Cancer Res. 59:4104-4110.

L. S. Musil, B. A. Cunningham, G. M. Edelman, and D. A. Goodenough (1990). Differential phosphorylation of the gap junction protein connexin43 in junctional communicationcompetent and-deficient cell lines. J. Cell Biol. 111:2077-2088.

W. M. Jongen, D. J. Fitzgerald, M. Asamoto, C. Piccoli, T. J. Slaga, D. Gros, M. Takeichi, and H. Yamasaki (1991). Regulation of connexin 43-mediated gap junctional intercellular communication by Ca2+ in mouse epidermal cells is controlled by E-cadherin. J. Cell Biol. 114:545-555.

R. A. Meyer, D.W. Laird, J. P. Revel, and R.G. Johnson (1992). Inhibition of gap junction and adherens junction assembly by connexin and A-CAM antibodies. J. Cell Biol. 119:179-189.

M. Hsu, T. Andl, G. Li, J. L. Meinkoth, and M. Herlyn (2000). Cadherin repertoire determines partner-specific gap junctional communication during melanoma progression. J. Cell Sci. 113:1535-1542.

M. A. van der Heyden, M.B. Rook, M. M. Hermans, G. Rijksen, J. Boonstra, L. H. Defize, and O. H. Destree (1998). Identification of connexin43 as a functional target for Wnt signalling. J. Cell Sci. 111:1741-1749.

L. Koffler, S. Roshong, P. Kyu, I. K. Cesen-Cummings, D. C. Thompson, L. D. Dwyer-Nield, P. Rice, C. Mamay, A. M. Malkinson, and R. J. Ruch (2000). Growth inhibition in G(1) and altered expression of cyclin D1 and p27(kip-1) after forced connexin expression in lung and liver carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biochem. 79:347-354. (Process Citation)

S. C. Chen, D. B. Pelletier, P. Ao, and A. L. Boynton (1995). Connexin43 reverses the phenotype of transformed cells and alters their expression of cyclin/cyclin-dependent kinases. Cell Growth Differ. 6:681-690.

D. B. Gros and H. J. Jongsma (1996). Connexins in mammalian heart function. Bioessays 18:719-730.

R. Dermietzel and D. C. Spray (1993). Gap junctions in the brain:Where, what type, how many and why? Trends Neurosci. 16:186-192.

H. J. Donahue, Z. Li, Z. Zhou, and C. E. Yellowley (2000). Differentiation of human fetal osteoblastic cells and gap junctional intercellular communication. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol 278:C315-C322.

W. R. Lowenstein and Y. Kanno (1966). Intercellular communication and the control of tissue growth: Lack of communication between cancer cells. Nature 209:1248-1249.

I. S. Fentiman (1980). Cell communication in breast cancer. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 62:280-286.

W. R. Loewenstein (1979). Junctional intercellular communication and the control of growth. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 560:1-65.

V. Krutovskikh, G. Mazzoleni, N. Mironov, Y. Omori, A. M. Aguelon, M. Mesnil, F. Berger, C. Partensky, and H. Yamasaki (1994). Altered homologous and heterologous gapjunctional intercellular communication in primary human liver tumors associated with aberrant protein localization but not gene mutation of connexin 32. Int. J. Cancer 56:87-94.

I. V. Budunova and G. M. Williams (1994). Cell culture assays for chemicals with tumor-promoting or tumor-inhibiting activity based on the modulation of intercellular communication. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 10:71-116.

H. S. Rosenkranz, N. Pollack, and A. R. Cunningham (2000). Exploring the relationship between the inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication and other biological phenomena. Carcinogenesis 21:1007-1011.

M. Rosenkranz, H. S. Rosenkranz, and G. Klopman (1997). Intercellular communication, tumor promotion and nongenotoxic carcinogenesis: Relationships based upon structural considerations. Mutat. Res. 381:171-188.

V. A. Krutovskikh, M. Oyamada, and H. Yamasaki (1991). Sequential changes of gap-junctional intercellular communications during multistage rat liver carcinogenesis: Direct measurement of communication in vivo. Carcinogenesis 12:1701-1706.

H. Yamasaki (1990). Gap junctional intercellular communication and carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 11:1051-1058.

S. A. Garber, M. J. Fernstrom, G. D. Stoner, and R. J. Ruch (1997). Altered gap junctional intercellular communication in neoplastic rat esophageal epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis 18:1149-1153.

C. Tomasetto, M. J. Neveu, J. Daley, P. K. Horan, and R. Sager (1993). Specificity of gap junction communication among human mammary cells and connexin transfectants in culture. J. Cell Biol. 122:157-167.

S. W. Lee, C. Tomasetto, D. Paul, K. Keyomarsi, and R. Sager (1992). Transcriptional downregulation of gap-junction proteins blocks junctional communication in human mammary tumor cell lines. J. Cell Biol. 118:1213-1221.

K. K. Hirschi, C. E. Xu, T. Tsukamoto, and R. Sager (1996). Gap junction genes Cx26 and Cx43 individually suppress the cancer phenotype of human mammary carcinoma cells and restore differentiation potential. Cell Growth Differ. 7:861-870.

K. K. Wilgenbus, C. J. Kirkpatrick, R. Knuechel, K. Willecke, and O. Traub (1992). Expression of Cx26, Cx32 and Cx43 gap junction proteins in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Int. J. Cancer 51:522-529.

G. P. Robertson, A. B. Coleman, and T.G. Lugo (1996). Mechanisms of human melanoma cell growth and tumor suppression by chromosome 6. Cancer Res. 56:1635-1641.

M. P. Piechocki, R. D. Burk, and R. J. Ruch (1999). Regulation of connexin32 and connexin43 gene expression by DNA methylation in rat liver cells. Carcinogenesis 20:401-406.

L. S. Musil, A. C. Le, J. K. VanSlyke, and L. M. Roberts (2000). Regulation of connexin degradation as a mechanism to increase gap junction assembly and function. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25207-25215.

B. Rose, P. P. Mehta, and W. R. Loewenstein (1993). Gapjunction protein gene suppresses tumorigenicity. Carcinogenesis 14:1073-1075.

T. J. King, L. H. Fukushima, T. A. Donlon, A. D. Hieber, K. A. Shimabukuro, and J. S. Bertram (2000). Correlation between growth control, neoplastic potential and endogenous connexin43 expression in HeLa cell lines: Implications for tumor progression. Carcinogenesis 21:311-315.

D. Zhu, G. M. Kidder, S. Caveney, and C. C. Naus (1992). Growth retardation in glioma cells cocultured with cells overexpressing a gap junction protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89:10218-10221.

R. P. Huang, Y. Fan, M. Z. Hossain, A. Peng, Z. L. Zeng, and A. L. Boynton (1998). Reversion of the neoplastic phenotype of human glioblastoma cells by connexin 43 (cx43). Cancer Res. 58:5089-5096.

V. A. Krutovskikh, S. M. Troyanovsky, C. Piccoli, H. Tsuda, M. Asamoto, and H. Yamasaki (2000). Differential effect of subcellular localization of communication impairing gap junction protein connexin43 on tumor cell growth in vivo. Oncogene 19:505-513.

D. L. Dankort and W. J. Muller (2000). Signal transduction in mammary tumorigenesis: A transgenic perspective. Oncogene 19:1038-1044.

R. Heimann and S. Hellman (2000). Individual characterisation of the metastatic capacity of human breast carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer 36:1631-1639.

J. Yokota (2000). Tumor progression and metastasis. Carcinogenesis 21:497-503.

J. Russo and I. H. Russo (2001). The pathway of neoplastic transformation of human breast epithelial cells. Radiat. Res. 155:151-154.

R. Engers and H. E. Gabbert (2000). Mechanisms of tumor metastasis: Cell biological aspects and clinical implications. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 126:682-692.

M. J. Seraj, R. S. Samant, M. F. Verderame, and D. R. Welch (2000). Functional evidence for a novel human breast carcinoma metastasis suppressor, BRMS1, encoded at chromosome 11q13. Cancer Res. 60:2764-2769.

A. Navolotski, A. Rumjnzev, H. Lu, D. Proft, P. Bartholmes, and K. S. Zanker (1997). Migration and gap junctional intercellular communication determine the metastatic phenotype of human tumor cell lines. Cancer Lett. 118:181-187.

G. L. Nicolson, K. M. Dulski, and J. E. Trosko (1988). Loss of intercellular junctional communication correlates with metastatic potential in mammary adenocarcinoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85:473-476.

J. Hamada, N. Takeichi, and H. Kobayashi (1988). Metastatic capacity and intercellular communication between normal cells and metastatic cell clones derived from a rat mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res. 48:5129-5132.

J. Hamada, N. Takeichi, J. Ren, and H. Kobayashi (1991). Junctional communication of highly and weakly metastatic variant clones from a rat mammary carcinoma in primary and metastatic sites. Invasion Metastasis 11:149-157.

J. Ren, J. Hamada, N. Takeichi, S. Fujikawa, and H. Kobayashi (1990). Ultrastructural differences in junctional intercellular communication between highly and weakly metastatic clones derived from rat mammary carcinoma. Cancer Res. 50:358-362.

M. M. Saunders, M. J. Seraj, Z. Li, Z. Zhou, C. R. Winter, D. R. Welch, and H. J. Donahue (2001). Breast cancer metastatic potential correlates with a breakdown in homospecific and heterospecific gap junctional intercellular communication. Cancer Res. 61:1765-1767.

A. Shoji, Y. Sakamoto, T. Tsuchiya, K. Moriyama, T. Kaneko, T. Okubo, M. Umeda, and K. Miyazaki (1997). Inhibition of tumor promoter activity toward mouse fibroblasts and their in vitro transformation by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1). Carcinogenesis 18:2093-2100.

W. H. Fletcher, W. W. Shiu, T. A. Ishida, D. L. Haviland, and C. F. Ware (1987). Resistance to the cytolytic action of lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor coincides with the presence of gap junctions uniting target cells. J. Immunol. 139:956-962.

M. E. el Sabban and B. U. Pauli (1994). Adhesion-mediated gap junctional communication between lung-metastatatic cancer cells and endothelium. Invasion Metastasis 14:164-176.

A. Ito, F. Katoh, T. R. Kataoka, M. Okada, N. Tsubota, H. Asada, K. Yoshikawa, S. Maeda, Y. Kitamura, H. Yamasaki, and H. Nojima (2000). A role for heterologous gap junctions between melanoma and endothelial cells in metastasis. J. Clin. Invest. 105:1189-1197.

Y. Kamibayashi, Y. Oyamada, M. Mori, and M. Oyamada (1995). Aberrant expression of gap junction proteins (connexins) is associated with tumor progression during multistage mouse skin carcinogenesis in vivo. Carcinogenesis 16:1287-1297.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carystinos, G.D., Bier, A. & Batist, G. The Role of Connexin-Mediated Cell–Cell Communication in Breast Cancer Metastasis. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 6, 431–440 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014787014851

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014787014851